Please note nearly all images are under copyright and can only be used with the owner's agreement.

Colin Montgomery

Born 23 June 1963

Probably the greatest Scottish player to never win a major title. His career features two achievements that may never be beaten. Despite his disappointments in the majors, Montgomerie is heralded as one of the greatest Ryder Cup players of all time, but even this is overshadowed by his eight European order of merit wins; seven of which were in succession.

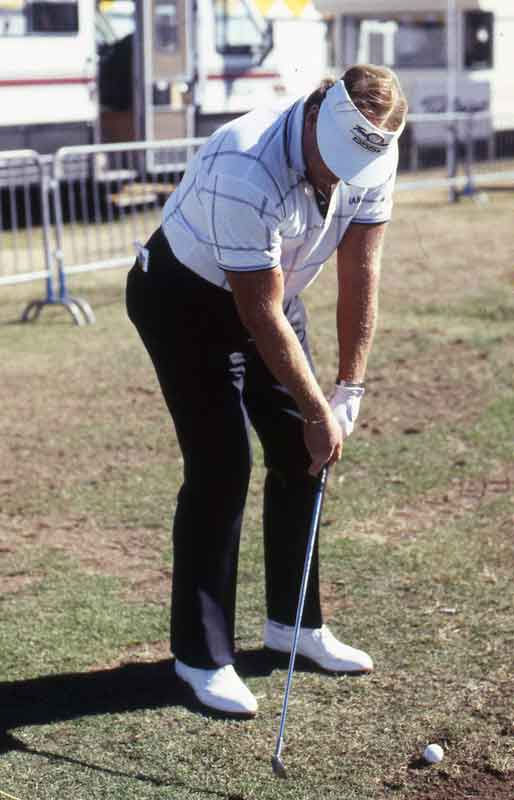

Long iron swing

To start this swing analysis I have to use a small discussion I had about Monty with the late Bernard Cooke, author of several books and teacher to some of the best players in Europe: Although hugely successful in his career Bernard felt the swing of Montgomery could not be used as a model for other players, and in particular normal handicap golfers. Basically, Bernard said that his swing action was turned the wrong way around and Montgomery was probably the most successful slicer in the history of the golf game.

The photo study shows how Monty hooded the clubface in his start back. His right hand is now in a very weak position as it resists the natural motion that his bones and joints would make in a standard Tour Pro swing.

eg. The movement of the right elbow joint contributes to the shut-to-open motion and tilt, rather than the turn, of the shoulders.

From a 45° angle, we can see the corresponding effects on his trunk response, which tilts rather than turns. The right elbow joint is separating and is now, like his hips, out of plane.

Montgomery`s arms are soft rather than firm, which he acknowledges when explaining his swing thoughts. His stance is on the narrow side, which conforms to the rest of his mechanics. He also prefers an extra light grip and focuses on swinging the clubhead without any interfering extras (see article on Ernest Jones).

At the top, we see a fair amount of recovery has corrected most of the early faults. The 'cupped' left wrist, while the club face is now square, is not necessarily a fault anymore.

At this point, Monty shows superb poise. He is in no hurry to rush back at the ball. Although many would argue there is no stop in a golf swing, most of the best players get close.

From a frontal angle, the closed-to-open action can be seen more clearly (it makes no difference if it is a wood or iron swing). The body is tilted slightly left as both knees 'give' to the right. This is all an effect that began in the early part of the swing.

Nevertheless, Monty's back was facing the target with his shoulders making a 100° turn. His beautiful poise is also clearly evident from this angle.

This high-speed film records the Montgomery Driver swing from 25 years ago while at the height of his game.

Unfortunately, this film was taken close to darkness and is not of the highest quality. Nevertheless, we can see the factors that are of interest. Monty shows no differences in his swing, whether driver or iron, last year or twenty years ago. He also used the same mechanics for his short game. Chips, pitches, and even putting followed the clubface opening through contact.

In the start forward Monty leaves his leisurely swing behind and applies a split-second change of dynamics. His lower body leads the upper trunk which responds in unity. The arms remain passive and follow. Even the facial expressions confirm his more energetic attack.

The Montgomery release is back on track. He has no interest in the ball as he continues to take the swing to its conclusion. In his own words, he wants to make the ball "incidental," something that happens to be there as he swings around his body. He also said he prefers an upright motion, leaving no chance for his arms to get behind him.

Summary

Montgomery`s record is one of consistency. He played a low fade throughout his career. He was not interested in making changes in his swing mechanics, preferring to groove a working swing to perfection. Nobody can know what sort of record he would have achieved had he used more conforming mechanics.

That is the question for this forum. The natural response is how can you put Montgomery`s mechanics down as the reason for his constant failure when it mattered, he was a proven champion? Was it more a mental problem? Was it sometimes because of his inability in the last stages to shape shots? It would be great to hear the opinions of swing historians and anybody who has an interest in the mechanics of golf.

Gordon J. Brand Jnr (19 August 1958 – 31 July 2019)

Known for his humour and forthrightness Gordon Brand Junior left us far too early. A heart attack at the age of 60, while resting during a playing event stunned the Champions League Tour with its suddenness.

Wedge swing

The film shows why Brand was known as one of the best ball strikers of his day. Unhurried and smooth he made a simple back and through movement.

The gentle rolling of the feet created a solid base for the shoulders to turn with speed. Likewise, his left arm remained firm through the contact area and continued counterwinding beyond the ball. This clearly shows why he struck the ball so well.

5 iron

The wedge and 5 iron swings are difficult to separate with only a careful look at the different lengths of the shafts giving it away.

The backswing summit with a 5 iron. Hands are high rather than wide. The right knee resists and ensures he stays on center and well-balanced.

Driver swing analysis The final film shows the flawless driver-swing action of Gordon Brand Jr.

Brian Barnes

3 June 1945 – 9 September 2019

One of the great characters of professional golfing history.

With a pipe in his mouth and a bottle of vodka after the round, Brian Barnes, who died aged 74 of cancer, cut a colorful, instantly recognizable figure on the European golfing circuit during his 1970s heyday.

Barnes was born in Addington Surrey, England, by Scottish parents, and represented England at the amateur international level. He was educated at St. Dunstan's, Burnham-on-Sea, and Millfield School in Somerset.

Taught by his father Barnes represented England in the youth international against Scotland in 1964. In the same year, he turned professional.

Also in 1964, after his promising career start, Barnes was enrolled in a special training program designed to develop a future British Open champion.

Photo: In the early days. The 1951 Open winner Max Faulkner acted as coach. (Brian cuts a sturdy figure at the back).

Financed by entrepreneur Ernest Butten the participants became known as the Butten boys.

The Barnes swing, like the man himself, doesn`t always pay attention to the rules.

The most significant deviation was how he started his swing. With a forward press( mostly used to relieve tension and inject life into the beginning) that complicated the motion, Barnes used the small muscles from the word go.

The early wrist break narrowed the Barnes swing arc and contributed to a shorter backswing. The photo shows that Brian Barnes was still able to find a good position at the top, belying the standard rules.

After a short pause at the top Barnes returns with the knees first, and, like many top players with `shorter backswings,` he collects more wrist angle on the return.

Contact and Beyond shows how well Brian Barnes stays down on the ball and allows the swing path to circle back to the inside. His right shoulder continues to rotate, ensuring his wrists are not over-active.

THE FINISH

Sandy Lyle

One of the great players of the eighties he will always be remembered for his Open win at Royal St Georges in 1985, and his great fairway bunker shot to win the Masters. Sandy was the first British winner since Tony Jacklin in 1969 and continued the rise of European golfers in the world scene.

Sandy Lyle-(born 9 February 1958) has won two major championships during his career.

In 1977 Sandy turned professional and decided to represent Scotland. His first professional win came in the 1978 Nigerian Open, and he also won the Sir Henry Cotton Award as European Rookie of the Year that season. Lyle attained the first of an eventual 18 European Tour titles in 1979.